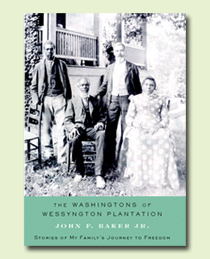

Joseph Washington and Mary Cheatham Washington.

Joseph came to Tennessee from Virginia and founded Wessyngton Plantation in 1796.

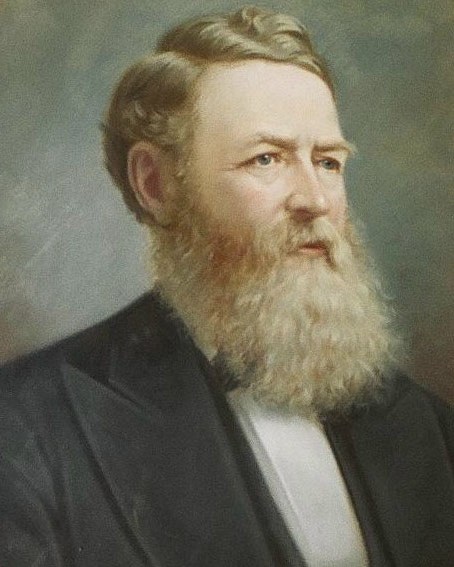

George A. Washington and Jane Smith Washington.

George inherited Wessyngton at his father's death in 1848 and increased Wessyngton until it became America's largest tobacco plantation.

Wessyngton mansion, 2007.

Restored slave cabin on Wessyngton Plantation.

In 1860 forty log cabins housed a labor force of 274 slaves.

Washington Hall built 1897 by George A. Washington, Jr.

The 44-room mansion was one of the show places of the South. Some of the crowned heads of Europe were entertained there.

Glenraven mansion built 1897.

Home of the Washington's daughter Jane Washington Ewing.

JOHN BAKER UNRAVELS HISTORY

Genealogy Expert John F. Baker Jr., has written the most accessible and exciting work of African American history since Roots.

John F. Baker Jr. tells the story of his great-great-grandparents who were enslaved on Wessyngton Plantation owned by the Washington family as well as the story of the hundreds of African Americans connected with Wessyngton Plantation for more than two hundred years.

Joseph Washington a cousin of President George Washington from Southampton County, Virginia founded Wessyngton Plantation outside of Nashville, Tennessee in 1796. By 1860 it was not only the largest tobacco plantation in America but also the second largest tobacco plantation in the world. It encompassed more than 15,000 acres in two states and had a slave population of 274 (the largest in Tennessee). When the family sold Wessyngton Plantation in 1983, it was the largest farm in America owned by direct descendants of the original founder. Wessyngton Plantation, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is a working farm. The mansion, built brick by brick by its slaves, still stands as does a slave cabin and its slave cemetery.

For the most part, the Washingtons did not sell their slaves so the slaves formed family groups that stayed intact for generations, in many cases to the present time. Both Joseph Washington and his son, George Augustine Washington, allowed some of their slaves to use true African names, which was very rare for that period. This has made it possible to trace their African ethnic group heritage, which has been confirmed by DNA testing. After the Civil War the Washington family continued its connection to their former slaves and their descendants. Many freedmen adopted the Washington surname after emancipation while others used names of previous owners or their own family connections.

The Washington family commissioned portraits of several of their former slaves at the end of the nineteenth century. Portraits by Maria Howard Weeden hung in prominent places in the Wessyngton mansion and in the plantation homes of the Washington children, Washington Hall and Glenraven. Weeden painted one portrait from an 1849 photograph of Henny Jackson Smith who was the servant of George A. Washington's wife, Jane Smith, and came from the Forks of Cypress Plantation in Alabama. Alex Haley's ancestors were slaves on that plantation and the subject of his book Queen. Weeden painted another portrait of Baker's ancestor, Emanuel Washington (1824-1907). Wessyngton slaves and their descendants used a 200-grave slave cemetery on the plantation up to the late 1920s. In 1995 descendants of the plantation owners erected a monument there to memorialize it. Wessyngton slave descendants founded an association in 1935. The association members and other descendants visit the plantation to learn about their distant past.

Dozens of photographs and even portraits of African Americans who were slaves on the plantation bring this compelling American history to life. Oral histories and thousands of written records give fresh insight into this history with national implications. The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation is in an uplifting story of survival and family; it honors the memory of the slaves, their struggles and their achievements.

Unique Aspects of The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation

Previously unpublished photographs. More than fifty extraordinary photographs and portraits of Wessyngton Plantation slaves, some dating back to the pre-Civil War era and their descendants illustrate the text.

Drawn almost completely from primary documents. Seventy rolls of microfilm of the thousands of pages in the Washington Family Papers are housed in the Tennessee State Library and Archives in Nashville. It is one of the few complete plantation collections in the country and the only one in the state library. These papers are remarkable in their content and included slave birth registers (1795 to 1860), tax records listing slave names, diaries, letters, slave bills of sales, food and clothing allocations, and inventories.

In depth oral cultural history. Baker interviewed more than twenty-five children and grandchildren of Wessyngton slaves gathering wonderful family stories; some of them had known their ancestors who had lived under slavery. He and these individuals have various decorative items once belonging to the plantation owners.

Two centuries of continuity. More than twenty former slave families worked on Wessyngton as sharecroppers, servants, and artisans after the Civil War; a few families purchased former Wessyngton farmland and many still live in the area.

Significant historical connections. Not only is Wessyngton Plantation connected with the family of George Washington, but also the families in Alex Haley's Queen and Robert Hicks' Widow of the South. In addition the family had political, economic, and personal connections to President Andrew Jackson, his Kitchen Cabinet and the Hermitage Plantation.