http://www.berkshirefinearts.com/05-12-2014_slaves-and-slaveholders-of-wessyngton-plantation.htm

Posts Tagged ‘slave trade’

SLAVES AND SLAVEHOLDERS OF WESSYNGTON PLANTATION EXHIBIT TOUR

Tuesday, May 13th, 2014Digitalization of Southampton County Virginia Records Opens New Doors for African American Research

Sunday, April 17th, 2011The entire Court Order book collection of the Southampton County, Virginia Court from 1749 through the early 1880s has been digitalized. This includes 57,000 pages, involving approximately one million names. This information is free online at: www.wiki.familysearch.org/en/Southampton_County,_Virginia. This collection is a goldmine for African Americans tracing their ancestors who once lived in Southampton County. Many of the books that have been digitized were 300 to 700 pages. Court Order books from the 1700s to the end of the slave trade lists the names of Africans when they were first brought to the area, their ages, owner’s names, and in a few cases the ships on which they were brought over. Wills and estate settlements lists the names of slaves, descriptions and family relationships. If your ancestors came from Southampton County, Virginia, you must check out this collection. Thanks go to Southampton Circuit Court Clerk, Richard Francis, and the volunteers of the Brantley Association of America who undertook this huge project in 2009 and 2010.

Court Case Reveals Plight of Africans During the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Wednesday, April 7th, 2010The following story sheds light on the impact of the Transatlantic slave trade on the lives of native Africans. Some of these slaves ended up on the plantations of the Blow families.

I found this story while searching through a Sussex County deed book looking for genealogical information and noticed the names of several slaves. What stood out most were the names of some of the slaves: August, September, June, April, Caesar, and Quaco. I then thought these were likely Africans. Some slave owners gave Africans the names of the months of the year or days of the week. Planters did not realize in some African cultures children were named for the days of the week they were born on, thereby continuing an African tradition. Names such as Samba, meaning born on Monday, which was later, corrupted to Sambo.

The plight of the Africans was revealed in detail in a Virginia court case that lasted eighteen years. The story began in 1781 during the Revolutionary War. John Wigfall owned a large plantation at Wambaw on St. Thomas Parish in South Carolina. During this time, Wigfall was a Loyalist to Britain and was banished from the colony and had his property confiscated which included his slaves. At the same time, Captain John Singletary was issued a commission as a privateer in his cutter Victory. His commission ordered him to take as prize any British property. Captain Singletary and a small crew set out in rowboats up the Santee River and landed at Wigfall’s plantation, where they captured thirty-four of his slaves: April, Will, August, Dolly, September, Wally, Philander, Philis, Caesar, Horah, Scipio, Cloey, Daniel, Santon, Will, Neppy, June, Dianah, Pegg, Binah, Jenny, Peter, Cyrus, Duke, Flora, Limbrick, Pharo, Toby, Nanny, Sabina, Rosanna, Carolina, Wallis, and Quashilla.[1][1] The slaves at first were taken to Beaufort, North Carolina.

Although Wigfall was to be banished, he was granted leniency because he pleaded poor health and a large family to support and was allowed to remain in South Carolina. Thus, Wigfall made immediate application for the return of his slaves, as a Court of the Admiralty convened in New Bern and ruled that the slaves were a fair prize. They were declared property legally condemned by the court.

After discovering that Beaufort was threatened by the British, Singletary took the slaves to Virginia and sold them to four planters: Richard Blow of Sussex County, who was the nephew of Colonel Michael Blow, Colonel Benjamin Baker of Nanesmond County, Captain Sinclair in Smithfield, and William Hines of Southampton.

Wigfall was informed of the whereabouts of some of the slaves and managed to steal back a few of them, although some of their names had been altered to conceal their identities. Wigfall and his son and the plantation owners had several heated disputes over the ownership of the slaves.

In 1792, John Wigfall gave his friend James Warrington of Richmond power of attorney to recover his property, to no avail. In 1798 his son Joseph, who was the executor of his estate pursued the case. The judgment in all matters of the case except the ownership of the slaves was in favor of the defendants. However, each purchaser had to pay Wigfall for the use of the slaves during the time they were in Virginia.

Some forty years later some of the Africans were still living on Richard Blow’s plantation in Sussex County called Tower Hill. An 1830s register of slaves for Tower Hill lists August, Tember (September) and April, who was also called Joe, (possibly a shortened version of the African day name Cudjo) as being African Negroes. They died in 1832, 1826, and 1829 respectively, ranging in age from 60 to 80.[2][2] Their names first appeared on tax lists for 1784 for Richard Blow when they were purchased.[3][3]

August probably suffered the greatest loss of all the Africans. According to descendants of the Blows, after August learned English he and the other Africans related the story of their capture and voyage from Africa. August informed the Blow family that his father was an African king and he was next in line to succeed him to the throne but was betrayed by a jealous uncle who sold him to slave traders so he could rule as king. Instead of living the life of African nobility, August was condemned to a life of American servitude.

[1][1] Power of Attorney from John Wigfall to James Warrington 1792 to recover slaves taken from his Wambaw plantation in South Carolina, Sussex County Deed Book G pages 723-725. Federal District Court case, Richmond, VA Wigfall Vs Blow 1799, Virginia State Library and Archives.

[2][2] Register of slaves on the plantations of Richard Blow 1832. 1838 register of slaves of George Blow. Manuscripts Department of Swem Library, College of William and Mary. Register contains the slaves’ names, parents’ names, dates of birth and death, if the slave was acquired by inheritance, purchase or gift.

[3][3] 1784 Tithables for Sussex County, VA for Richard Blow. Virginia State Library and Archives.

Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation: Stories of My Family’s Journey to Freedom – Resource for Educators and Teachers

Tuesday, February 9th, 2010The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation: Stories of My Family’s Journey to Freedom has been released in trade paperback and is an excellent resource for teachers and educators. The book chronicles the African American experience from slavery to freedom. It has more than 100 photographs and portraits of African Americans who were once enslaved. The book covers many aspects of plantation slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, Genealogy, and DNA testing.

http://books.simonandschuster.net/Washingtons-of-Wessyngton-Plantation/John-F-Baker-Jr/9781416567417

Nat Turner’s Rebellion of 1831

Monday, December 21st, 2009In 1831, Nat Turner led the largest slave rebellion in the history of the United States. Turner, born in 1800 in Jerusalem, Southampton County, Virginia. Wessyngton Plantation’s founder Joseph Washington lived in Southampton County before he came to Tennessee. Many of the slaves on Wessyngton Plantation were brought by Joseph to Tennessee.

In Virginia, Turner, a self-proclaimed Baptist minister, was known as “The Prophet” to the enslaved African Americans and often conducted services for them. He claimed to be given visions by God, and that he was ordained to lead his people to freedom. Unlike most slaves and many whites, Turner was able to read and write.

Turner’s group of followers was composed of more than 50 fellow slaves and free blacks. During the insurrection of 1831, the group went through the countryside of Southampton County killing 55 men, women, and children. The insurrection lasted for two days before the local militia put it down. Turner and several of the leaders were executed; others were transported out of the area.

The Turner rebellion put fear in the hearts and minds of slave holders throughout the South, which led to laws further restricting the activities of enslaved African Americans and free blacks.

The revolt influenced the Tennessee legislature to pass laws in 1831 that prevented more free blacks from entering the state. Any person emancipating a slave had to send him out of the state. When the new constitution in Tennessee was written in 1834, free blacks were denied voting privileges.

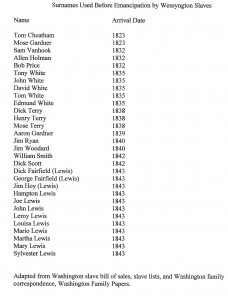

Use of Surnames Among African Americans Before Emanicaption

Tuesday, November 10th, 2009Slaves were usually known by their first names, especially on small farms with few slaves. Plantation owners rarely recorded their slaves with surnames unless they had several individuals with the same first names. For that reason the use of surnames by slaves was far more common on large plantations where more people were likely to have the same given names.

Due to Wessyngton Plantation having such a large enslaved population many African Americans are listed with their previous owners’ surnames as early as the 1820s.

Slave bills of sale and other documents in the Washington Family Papers collection details the origins of many of these African American families.

The list above documents the names African Americans on Wessyngton Plantation who used surnames prior to emancipation and the date of their arrival on the plantation.

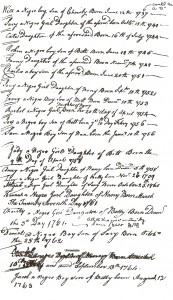

Slave Owner’s Family Bible Documents Slave Births During the 1700s

Monday, October 26th, 2009Slave owners kept detailed records of their slaves’ births, and deaths, and purchases; although many of them have not survived. They often recorded these events in their family bibles along with information on their own families.

The 1715 Blow family bible records the births of slaves owned by the Blows of Sussex, and Southampton counties in Virginia. Nineteen births of four mothers are recorded from 1737 to 1763 spanning three generations. This is a goldmine of information for African American research. Descendants of these slaves can be found searching other records in the Blow Family Papers in the Swem Library in Virginia.

Slave Women on Southern Plantations

Friday, October 9th, 2009Enslaved African American women performed various task on southern plantations and farms. Women on Wessyngton Plantation were not required to do any hard labor in the fields as the men did; however, they were an important part of other operations on the plantation. Women did light work in the gardens, they knitted and sewed for the slave community and their owners, worked the looms, and did the spinning and weaving. They were responsible for cooking, cleaning, washing, ironing, making cheese, preserves, and soap. No mother with a young baby was expected to do any outside work until her baby was two years old. There was a nursery on the plantation were children were cared for by elderly women too old to work. Women were a vital part of the pork processing industry on the plantation as seen in the photo above. Each week the women on the plantation would assemble at the plantation smokehouse (building in background of photo) and would be allotted bacon, meal, flour, sugar, and coffee based on the number of individuals in their families. Hundreds of hogs were killed at each year at Wessyngton to feed the enslaved population and the Washington family. Wessyngton had a reputation for producing its famous Washington Hams which could be found on the menus of the finest restaurants as far south as New Orleans and as far north as Philadelphia.

Surnames Used by African American Slaves

Friday, August 28th, 2009There has been much debate among scholars, historians and genealogists whether enslaved African Americans used the surnames of their last owners, previous owners, or a surname that had no connection to slavery.

Location the owner of one’s ancestor is crucial for an African American genealogist to trace his family before 1870.

In more than thirty years of researching my ancestors and hundreds of others enslaved on one of America’s largest plantations, slaves owned by mid-sized planters and small farmers, reviewing thousands of documents I have come across various situations that might give others clues on what to look for.

There are many factors to consider in determining what surnames African Americans used.

Although it is not widely known, some African Americans used surnames before they were emancipated. This happened mostly on large plantations where several individuals had the same first names and a surname was used to distinguish them from one another.

African Americans were known by these surnames in the slave community and often recorded by slave owners on plantation documents.

In small communities where census takers and county officials knew African Americans personally and their previous owners, they often recorded the former slaves with the surnames of their last owners. One former slave Bill Scott from Wessyngton reported in his pension application for military service that when he enlisted in the Union Army officials put down his surname as Washington. He stated that he had always been known by his father’s surname Scott, even before he was freed.

Former slaves often made up surnames based on their occupations. A Wessyngton slave named Bill who was the plantation’s blacksmith was known as Billy the Smith during slavery. After emancipation, he became William Smith. Another slave named Bill who attended the sheep became Bill Shepherd.

When slave owners married, they often received slaves as wedding gifts and inheritances from their wife’s family. As a result, many slaves used the surnames of their owner’s wife’s family. When Wessyngton’s owner George A. Washington married Margaret Lewis in 1849 her father gave the couple twenty-nine slaves. The majority of these slaves used the surname Lewis instead of Washington. If searching for a slave owner with the same surname of your ancestor fails, check marriage records for the slave owners. This may reveal your family used the surname of the slave owner’s wife’s family.

African Americans tended to use surnames associated with their own families instead of the last slave owner. In the late 1830s, Nathaniel Terry of Todd County, Kentucky died leaving a plantation of fifty slaves. Five of the slaves were sold to the Washingtons and brought to Wessyngton. Several of the other slaves were sold to various slave owners. After emancipation, they all used the Terry surname because their families had been with the white Terry family for generations.

Former slaves also interchanged surnames on census records. It is not uncommon to see an African American family listed with one surname in 1870 and another in 1880. This is due in part to officials imposing surnames on them based on their last owners. John Lewis was born in 1831; in 1844 he and several family members were given to George A. Washington of Wessyngton. In 1870, he is listed as John Washington. On all subsequent census records, he is listed as John Lewis. This was the case with several others from Wessyngton.

Another myth is once African Americans were sold they never saw their families again. This is true in some cases but not all. In small communities when slaves were sold, they were often bought by someone in the area. Thomas Black Cobbs was owned by a small slave owner Catherine Black. At her death when Thomas was ten, he was sold to Solomon Cobbs who lived nearby. Thomas’ mother, younger brothers and sisters remained with the Black family. After emancipation, he moved back with his mother, brothers and sisters and used the Cobbs surname. It had always been passed down in the family that Thomas has been owned by the Blacks.

In instances where slaves were sold from their families and they did not retain their previous owners’ surnames, they named their children for parents, sisters and brothers to keep a connection with their families. In 1836, William Turbeville died leaving an estate with several slaves who were brothers: Turner, Nelson, Simon, Jordan, and Jacob. They were all sold to different owners: Connell, Rose, Johnson, and Hughes respectively. The brothers were sold when they were very young and remained with their last owners nearly thirty years. In 1870, all of them were listed with the surnames of their last owner; however, each one of them named their sons for one of their brothers.

Former slaves often used surnames names of historical figures such as Washington, Jefferson or Jackson. Others who wanted no connection to their former owners used surnames like Freeman or Freedman. In these cases, unless the name change had been passed down in the family by oral history, it would be impossible to trace the family back any further. This is another instance of oral history being a key component in tracing African American ancestry.