There has been much debate among scholars, historians and genealogists whether enslaved African Americans used the surnames of their last owners, previous owners, or a surname that had no connection to slavery.

Location the owner of one’s ancestor is crucial for an African American genealogist to trace his family before 1870.

In more than thirty years of researching my ancestors and hundreds of others enslaved on one of America’s largest plantations, slaves owned by mid-sized planters and small farmers, reviewing thousands of documents I have come across various situations that might give others clues on what to look for.

There are many factors to consider in determining what surnames African Americans used.

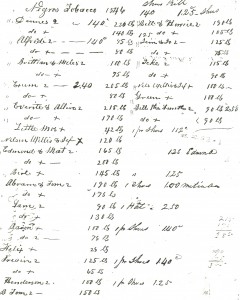

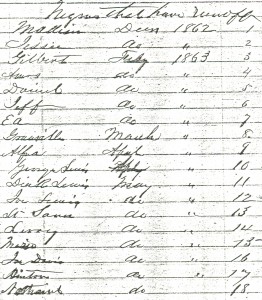

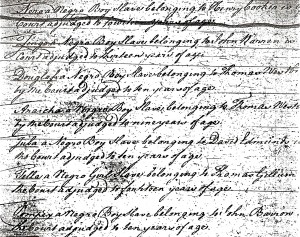

Although it is not widely known, some African Americans used surnames before they were emancipated. This happened mostly on large plantations where several individuals had the same first names and a surname was used to distinguish them from one another.

African Americans were known by these surnames in the slave community and often recorded by slave owners on plantation documents.

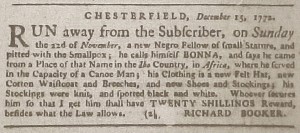

In small communities where census takers and county officials knew African Americans personally and their previous owners, they often recorded the former slaves with the surnames of their last owners. One former slave Bill Scott from Wessyngton reported in his pension application for military service that when he enlisted in the Union Army officials put down his surname as Washington. He stated that he had always been known by his father’s surname Scott, even before he was freed.

Former slaves often made up surnames based on their occupations. A Wessyngton slave named Bill who was the plantation’s blacksmith was known as Billy the Smith during slavery. After emancipation, he became William Smith. Another slave named Bill who attended the sheep became Bill Shepherd.

When slave owners married, they often received slaves as wedding gifts and inheritances from their wife’s family. As a result, many slaves used the surnames of their owner’s wife’s family. When Wessyngton’s owner George A. Washington married Margaret Lewis in 1849 her father gave the couple twenty-nine slaves. The majority of these slaves used the surname Lewis instead of Washington. If searching for a slave owner with the same surname of your ancestor fails, check marriage records for the slave owners. This may reveal your family used the surname of the slave owner’s wife’s family.

African Americans tended to use surnames associated with their own families instead of the last slave owner. In the late 1830s, Nathaniel Terry of Todd County, Kentucky died leaving a plantation of fifty slaves. Five of the slaves were sold to the Washingtons and brought to Wessyngton. Several of the other slaves were sold to various slave owners. After emancipation, they all used the Terry surname because their families had been with the white Terry family for generations.

Former slaves also interchanged surnames on census records. It is not uncommon to see an African American family listed with one surname in 1870 and another in 1880. This is due in part to officials imposing surnames on them based on their last owners. John Lewis was born in 1831; in 1844 he and several family members were given to George A. Washington of Wessyngton. In 1870, he is listed as John Washington. On all subsequent census records, he is listed as John Lewis. This was the case with several others from Wessyngton.

Another myth is once African Americans were sold they never saw their families again. This is true in some cases but not all. In small communities when slaves were sold, they were often bought by someone in the area. Thomas Black Cobbs was owned by a small slave owner Catherine Black. At her death when Thomas was ten, he was sold to Solomon Cobbs who lived nearby. Thomas’ mother, younger brothers and sisters remained with the Black family. After emancipation, he moved back with his mother, brothers and sisters and used the Cobbs surname. It had always been passed down in the family that Thomas has been owned by the Blacks.

In instances where slaves were sold from their families and they did not retain their previous owners’ surnames, they named their children for parents, sisters and brothers to keep a connection with their families. In 1836, William Turbeville died leaving an estate with several slaves who were brothers: Turner, Nelson, Simon, Jordan, and Jacob. They were all sold to different owners: Connell, Rose, Johnson, and Hughes respectively. The brothers were sold when they were very young and remained with their last owners nearly thirty years. In 1870, all of them were listed with the surnames of their last owner; however, each one of them named their sons for one of their brothers.

Former slaves often used surnames names of historical figures such as Washington, Jefferson or Jackson. Others who wanted no connection to their former owners used surnames like Freeman or Freedman. In these cases, unless the name change had been passed down in the family by oral history, it would be impossible to trace the family back any further. This is another instance of oral history being a key component in tracing African American ancestry.