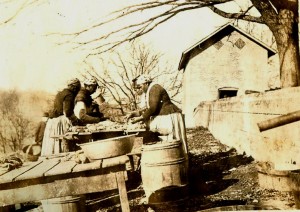

Enslaved African American women performed various task on southern plantations and farms. Women on Wessyngton Plantation were not required to do any hard labor in the fields as the men did; however, they were an important part of other operations on the plantation. Women did light work in the gardens, they knitted and sewed for the slave community and their owners, worked the looms, and did the spinning and weaving. They were responsible for cooking, cleaning, washing, ironing, making cheese, preserves, and soap. No mother with a young baby was expected to do any outside work until her baby was two years old. There was a nursery on the plantation were children were cared for by elderly women too old to work. Women were a vital part of the pork processing industry on the plantation as seen in the photo above. Each week the women on the plantation would assemble at the plantation smokehouse (building in background of photo) and would be allotted bacon, meal, flour, sugar, and coffee based on the number of individuals in their families. Hundreds of hogs were killed at each year at Wessyngton to feed the enslaved population and the Washington family. Wessyngton had a reputation for producing its famous Washington Hams which could be found on the menus of the finest restaurants as far south as New Orleans and as far north as Philadelphia.

Archive for the ‘Plantation Life’ Category

Slave Women on Southern Plantations

Friday, October 9th, 2009Slave Housing on Southern Plantations

Monday, October 5th, 2009Housing for slaves varied from plantation to plantation depending on the owners. Most slave quarters were generally arranged in avenues or streets and located behind the mansion or ‘Big House.’ They were strategically placed to give the owner or overseer a clear view of the slaves, so their activities could be easily monitored.

The slave settlement at Wessyngton Plantation, however, did not fit this pattern. The lack of a clustered settlement pattern at Wessyngton was somewhat unusual during antebellum times. This was primarily due to the hilly topography of the plantation. The scattered pattern gave the slaves at Wessyngton more freedom and made it far more difficult to keep them under constant surveillance.

Typically, slave housing at Wessyngton consisted of hand-hewn one-room log cabins measuring 20 by 20 square feet with brick end chimneys. Some cabins were 18 by 36 square feet. Each cabin had log flooring and a loft, where children slept.

Each cabin housed an average of six individuals. Family sizes varied depending on the number births, deaths and marriages.

Plantation Records Key Link to African American Past

Sunday, September 6th, 2009

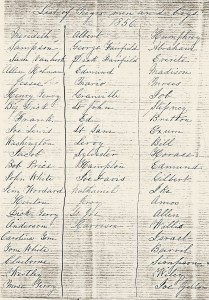

Plantation owners used records such as slave bills of sales, birth registers, and many other documents to keep an accurate count of their slaves’ births, deaths, and their production on plantations and farms. These documents are invaluable in tracing African American genealogy.

The document above is a list of enslaved African American men and boys on Wessyngton Plantation in 1856 owned by George A. Washington. Slave owners had to pay taxes on their slaves from age twelve to fifty, so the list only identifies those in that age range who were a part of the plantation labor force. Many of the individuals are listed with surnames: Davis, Fairfield, Gardner, Holman, Lewis, Price, Smith, Terry, Vanhook, White and Woodard. The use of these surnames made it possible to locate them and their previous slave owners. Many of them were also found on the 1870 U. S. Census living on or near Wessyngton Plantation.

In 1964, the Washington family deposited all their family papers and plantation records in the Tennessee State Library and Archives in Nashville. Hundreds of these documents shed light on the lives of hundreds of African Americans enslaved there.

A Thank You Letter from Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth

Tuesday, August 4th, 2009

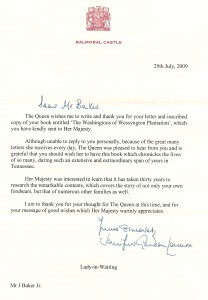

Queen Elizabeth acknowledged the receipt of a signed copy of my book. As is the custom, her lady-in-waiting wrote me. The royal seal indicated that the Queen was at her summer residence, Balmoral Castle in Scotland.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balmoral_Castle– for your info.

Colonial Documents Reveal African Roots

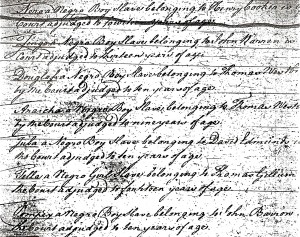

Friday, July 24th, 2009Nero a Negro boy slave belonging to Henry Cooker is by the court adjudged to fourteen years of age.

Zingo a Negro boy slave belonging to John Warren by the court adjudged to thirteen years of age.

Douglas a Negro boy slave belonging to Thomas Westbrooks by the court adjudged to ten years of age.

Anarcha a Negro boy slave belonging to Thomas Westbrooks by the court adjudged to nine years of age.

Juba a Negro boy slave belonging to David Edmunds by the court adjudged to ten years of age.

Tilla a Negro girl belonging to Thomas Gillum the court adjudged to fourteen years of age.

Pompey a Negro boy slave belonging to John Barrow the court adjudged to ten years of age.

During the Colonial period, slave owners were required to pay taxes on their slaves from ages twelve to fifty years old. When Africans were brought to the colonies and it was evident that they were adults they were simply added to tax rolls called tithables. When small children and teenagers arrived from Africa and their ages were uncertain, the slave owners would have to take them into court and a judge would assign an age for the slave, which was then recorded in minute or court order books. Most of the slaves were assigned English names, although some retained their true African names. Some of the court orders also list the names of the ships the Africans arrived in and the dates of arrival. Many of these individuals can be traced in later documents such as tax records, wills, and estate settlements. These records can prove to be a genealogical goldmine for African American researchers.

Using Colonial Records to Trace African American Genealogy

Friday, July 24th, 2009

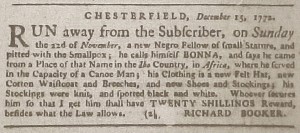

Virginia Gazette, Williamsburg, December 24, 1772

Chesterfield, December 15, 1772. Run away from the Subscriber, on Sunday the 22d of November, a new Negro Fellow of small Stature, and pitted with the Smallpox; he calls himself BONNA, and says he came from a Place of that Name in the Ibo Country, in Africa, where he served in the Capacity of a Canoe Man; his Clothing is a new Felt Hat, new Cotton Waistcoat and Breeches, and new Shoes and Stockings; his Stockings were knit, and spotted black and white. Whoever secures him so that I get him shall have TWENTY SHILLINGS reward, besides what the Law allows.

Richard Booker

A great source of tracing early African and African American ancestors is the Virginia Gazette. Slave owners ran ads describing in great detail their runaway slaves, apprentices and indentured servants. Many of these ads list native Africans, their ethnicities, country of origins, their owners, how long they had been in the colonies, and the ships they came on. These records are online at http://etext.virginia.edu/subjects/runaways/1740s.html.

Terry Family to Tour Wessyngton Plantation for Bi-Annual Reunion

Thursday, July 16th, 2009On Saturday August 8th the Terry family will tour Wessyngton Plantation as part of their bi-annual family reunion. The group will tour the Wessyngton slave cemetery, the Washington family cemetery, the grounds around the mansion and a restored slave cabin. Members of the National Black Arts Festival from Atlanta will also attend the reunion festivities. Following the tour the group will dine at the Tennessee National Guard Armory. I will also autograph copies of my new book The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation: Stories of My Family’s Journey to Freedom. The Terrys descend from Dick Terry 1818-1879 and Aggy Washington Terry born 1824. Today there are more than 1,000 Terry family members.

Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation Featured on BlackPast.org

Monday, July 13th, 2009Check out my article on BlackPast.org. It is an excellent resource for African American history and genealogy.

Enslaved African American Families on Wessyngton Plantation in 1860

Sunday, July 12th, 2009

In 1860 Wessyngton Plantation was the largest tobacco plantation in the United States. The Washington family also held the largest number of enslaved African Americans (274) in the state of Tennessee. 187 of them were held on what was called the “Home Place” near the Wessyngton mansion. Eighty-seven others were held on a part of the plantation known was the “Dortch Place.”

Runaways and Rebels on Wessyngton Plantation

Thursday, June 18th, 2009

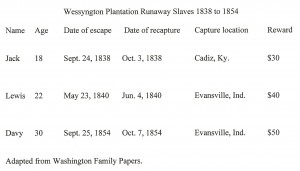

Wessyngton Runaways and Rebels

Enslaved African Americans used various forms of resistance against the institution of slavery. Some used passive forms of resistance such as pretending to be ill, secretly destroying tools, and work slow downs. Others used more drastic measures such as physical violence toward their enslavers and running away. Several men from Wessyngton Plantation escaped and made it to free territory. One slave Davy, ran away four times and was preparing to cross the Ohio River and go north to Canada when he was recaptured.